by Ryan Weber

Akayev's fall was based on long-simmering accusations of corruption as well as his restrictions on political freedoms - especially in the electoral process. Four months after Akayev fled Bishkek, the Kyrgyz people went back to the ballot box, this time to elect his successor. Almost 2 million citizens cast votes - a 74.67% turnout - in what was regarded by international observers as "tangible progress" toward "international standards for democratic elections." (OSCE/ODHIR, 2005)

Five years later, after the hero of the "Tulip Revolution" was himself overthrown for nepotism and authoritarian tendencies, the Kyrgyz again went to the polls, this time to indirectly elect a new chief executive - the Prime Minister. Initial reports were even more positive, despite pointing out the "urgent need for profound electoral legal reform" (OSCE/ODHIR, 2010) The 2010 Parliamentary election also set new records - the largest number of registered voters (over 3 million), and the lowest turnout in the country's history (55%).

The ramifications of this turn of events have been felt across the small country, as new electoral laws have caused for the first time the discrepancy between registered voters and ballots cast to influence the formation of government, as discussed earlier. Many, especially the Butun Kyrgyzstan party that was denied seats in Parliament as a result, have questioned the sudden addition of over 200,000 registered voters within the last month of the campaign. Such occurrences are not without precedent in Kyrgyzstan; both 2005 and 2009 saw approximately the same % increase in registered voters, but this was often attributed by international observers to administrative fraud, such as when the Bakiev regime approved exactly 114,000 new registrations from citizens living abroad - mostly in Russia - shortly before the 2009 vote.

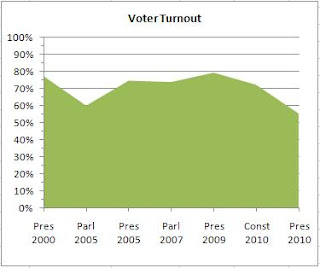

The ramifications of this turn of events have been felt across the small country, as new electoral laws have caused for the first time the discrepancy between registered voters and ballots cast to influence the formation of government, as discussed earlier. Many, especially the Butun Kyrgyzstan party that was denied seats in Parliament as a result, have questioned the sudden addition of over 200,000 registered voters within the last month of the campaign. Such occurrences are not without precedent in Kyrgyzstan; both 2005 and 2009 saw approximately the same % increase in registered voters, but this was often attributed by international observers to administrative fraud, such as when the Bakiev regime approved exactly 114,000 new registrations from citizens living abroad - mostly in Russia - shortly before the 2009 vote. If it was fraud before, how can we explain a similar phenomenon in the presumably less fraudulent post-Bakiev era?Going in the opposite direction, does the lack of administrative election tampering appropriately explain the significant drop-off in voter turnout, which averaged 72.91% in all elections from 2000 to the June 2010 Constitutional referendum, but just 55.27% in October 2010?

If it was fraud before, how can we explain a similar phenomenon in the presumably less fraudulent post-Bakiev era?Going in the opposite direction, does the lack of administrative election tampering appropriately explain the significant drop-off in voter turnout, which averaged 72.91% in all elections from 2000 to the June 2010 Constitutional referendum, but just 55.27% in October 2010?For starters, it will help to put perspective into the numbers themselves, and add a "3rd dimension" to quantitative analysis of Kyrgyzstan's electoral history.

Three Qualifiers for Comparing Kyrgyz Elections Over Time

On the practical front, such issues will certainly encourage Butun Kyrgyzstan and others to file complaints with the CEC on the grounds that, at the very least, something suspicious seems to be going on with the Kyrgyz voter lists. But analytically, we must also allow that, as is often the case in electoral democracy, even the highly improbably is not impossible.

To sort this all out, we must first acknowledge that statistics reported under known conditions of incumbent-engineered fraud cannot supply reliable figures, and this becomes more true the more specific we are. Even the temptation to use vague trends - to admit that an election had, if not a 79.35% turnout, at least a "high" turnout - can only be done cautiously, and bracketed with qualifiers.

Second, the reported election figures must be taken in consideration of their context, which is never static, and in the case of Kyrgyzstan, has shifted several times toward higher or lower degrees of political openness. Mapping election numbers, time, and now the 3rd dimension of political environment (roughly calculated as a "Fraud Index" on a 1 to 10 scale) produces new vistas for our consideration which are, appropriately, quite rocky, even mountainous (see below; in this rough attempt, shadow denotes decreases in the "fraud index"). In simple terms, the figures for periods of increased democratic openness, such as the 2005 Presidential and 2010 Parliamentary elections, should be given more weight, while those widely-criticized for opacity and fraud should be regarded more skeptically.

Finally, it is necessary to understand that the goal of administrative electoral fraud, at least in semi-authoritarian governments cloaking themselves in democratic garb such as is common in the Former Soviet Union, is not 100% approval and 100% turnout. While North Korea and other hard-line totalitarian states continue the Soviet practice of projecting solidarity through fabricated, even ridiculous, approval ratings, this is no longer the norm among savvy non-democratic, non-totalitarian states. More often, such countries strive to show through their manipulated figures a strong public participation - in the 70-85% turnout range - with allowances for a small opposition vote, say between 10-25%. Not only does this seem more credible to outside observers, but it allows the regime in power to write-off opposition voices and movements as a disgruntled, even radical, minority. Reports in the range of 70-80% turnout do not suggest a 20% "failure" of administrative elections fraud, but rather the ideal intended outcome. The 2009 Kyrgyz Presidential Election is a good example. In a vote that the OSCE/ODHIR mission descirbed as having, "failed to meet key OSCE commitments for democratic elections," Bakiev received 76% of the votes cast, compared with 16% for all opposition candidates combined, and the total voter turnout was reported at 79.38%.

Finally, it is necessary to understand that the goal of administrative electoral fraud, at least in semi-authoritarian governments cloaking themselves in democratic garb such as is common in the Former Soviet Union, is not 100% approval and 100% turnout. While North Korea and other hard-line totalitarian states continue the Soviet practice of projecting solidarity through fabricated, even ridiculous, approval ratings, this is no longer the norm among savvy non-democratic, non-totalitarian states. More often, such countries strive to show through their manipulated figures a strong public participation - in the 70-85% turnout range - with allowances for a small opposition vote, say between 10-25%. Not only does this seem more credible to outside observers, but it allows the regime in power to write-off opposition voices and movements as a disgruntled, even radical, minority. Reports in the range of 70-80% turnout do not suggest a 20% "failure" of administrative elections fraud, but rather the ideal intended outcome. The 2009 Kyrgyz Presidential Election is a good example. In a vote that the OSCE/ODHIR mission descirbed as having, "failed to meet key OSCE commitments for democratic elections," Bakiev received 76% of the votes cast, compared with 16% for all opposition candidates combined, and the total voter turnout was reported at 79.38%.What Happened in 2010, and What It Could Mean for Kyrgyzstan

From the 2000 Presidential election to the 2010 Constitutional Referendum, Kyrgyzstan has had a relatively stable number of registered voters and voter turnout, ranging from 2,470,000 to 2,775,000 and between 60% and 79% turnout (most often in the low 70s%). The 2010 Parliamentary election featured 3,002,508 eligible voters - the most ever registered - and also only 1,659,497 votes - among the fewest votes for any election this decade* (the total number of votes for the 2005 parliamentary and 2000 parliamentary elections are lacking, and may in fact be slightly below this figure). As a mathematical result, the subsequent turnout of 55% is the smallest in a decade as well.

From the 2000 Presidential election to the 2010 Constitutional Referendum, Kyrgyzstan has had a relatively stable number of registered voters and voter turnout, ranging from 2,470,000 to 2,775,000 and between 60% and 79% turnout (most often in the low 70s%). The 2010 Parliamentary election featured 3,002,508 eligible voters - the most ever registered - and also only 1,659,497 votes - among the fewest votes for any election this decade* (the total number of votes for the 2005 parliamentary and 2000 parliamentary elections are lacking, and may in fact be slightly below this figure). As a mathematical result, the subsequent turnout of 55% is the smallest in a decade as well.On the one hand, these results may represent the most accurate picture of Kyrgyz voting tendencies, having been conducted in what is universally heralded, even by its critics, as the most transparent and least fraudulent election in the country's history. The fall of the Bakiev regime in April 2010 and subsequent civil unrest in June created an atmosphere that was both charged for potential political change, but also demonstrated the weakness of the central government in Bishkek. Both factors could contribute to a hypothetical situation in which many Kyrgyz registered to vote for the first time, bouyed by the potential of change as Kyrgyz constitutionally became the first Parlimentary democracy in Central Asia. For the narrative to fit the numbers, this crowd would then have to be disillusioned by the ineffectiveness it witnessed over the summer, and by the time of the October 10 election, lost faith in the system, became apathetic, and neglected to cast ballots.

A more sinister read would be to point out how suspicious a break from all previous norms the 2010 results represent, especially the addition of over 200,000 voters to the registered voter lists in the closing days of the campaign. The large pool of eligible voters, and relatively small turnout, resulted in a denial of parliamentary inclusion for smaller parties - especially Butun Kyrgyzstan. It is not hard to imagine, nor without recent precedent, that improper voter registrations contributed to this increase, and thereby indirectly to the denial of government participation for BK. Having accepted such paranoid assumptions already, this would clearly be attributed to willful manipulation, not accident.

The case of Butun Kyrgyzstan, and the extremely small margin by which it was excluded - on an irregular technicality of the Electoral Code, no less - is certainly one that the party and its allies will continue to protest during the short review and contestation phase. The statistical discrepancy of the 2010 elections, especially in comparison to earlier results, provides ample fuel to those suspicious of a long-corrupt system, but perhaps we should be taking different lessons from the Kyrgyz electoral record.

But What Does It Really Mean?

First, it must be admitted that, of all its elections, Parliamentary elections always have lower turnout than Presidential elections. Historically, we could ascribe this to the fact that the Jorgorku Kenesh, parliament, whether in its uni- or bi-cameral form, was always of secondary importance to a strong centralized President.

This would align with the earlier assertion - backed strongly by the 2010 ODHIR preliminary report - that the low turnout figures present a more accurate reflection, not a less engaged citizenry.

As for the increase in the voter lists, there are reasonable explanations that both support and deny paranoid accusations. For starters, even using the final 2010 Parliamentary voter list tally of 3,002,508 we must acknowledge that the Kyrgyz population is almost twice as large - 5.5 million - and that many of the 2.5 Million unregistered citizens would be eligible to register if they so chose. In light of this figure, the potential for dramatic increases in the total number of registered voters is easily explained - even expected - if the populace suddenly became more enthusiastic about national politics. Dramatic regime change and internal ethnic violence would both qualify as such motivators.

In this light, a 200,000 person increase (7% of registered voters, but only 0.5% of the population) doesn't seem extreme at all. That is - until you compare it to voter increases in the past.

Between 2000 and the July 2010 Constitutional Referendum, the total number of registered Kyrgyz voters increased by only 190,754 (actually, from 2000 to 2009, it increased by 344,787, but was then reduced following Bakiev's removal when 245,983 named were rejected as invalid/unverifiable).

In 10 years, the Kygyz voter lists grew by less than 200,000. In the last month of the election, it creased by more than 200,000. Understandable why Butun Kyrgyzstan refuses to accept this as a natural occurence of increased Kyrgyz voter enthusiasm.

But was it anyway?

Conclusion

What it comes down to is this - in the face of a logically possible increase in Kyrgyz citizens wanting to register, then declining to vote, and an undeniable track record of improper tampering of voter lists - the question is, in this 2010 election, can we trust the Central Election Committee or not?

The evidence of voter list tampering under the semi- and increasingly authoritarian regimes of Bakiev and Akayev were noted by international observers, but in the face of blatant voter intimidation, ballot stuffing, multi-voting, and outright fabrications in the tabulation phase, earlier ODHIR reports have always mentioned voter list irregularities, but rarely made them a major focus. Under the previous electoral system, the number of registered votes was only indirectly relevant, as elections required 50% voter turnout to be valid. This of course could be easily achieved by fraudulent registrations casting illegal ballots - often in bulk - but there was no incentive to inflate registration numbers without also contributing to the active vote count.

In the post-Bakiev era, when international election observers credit the CEC with an overall very positive rating for their conduct, administration, and transparency of the vote itself, serious questions are being addressed for the first time to the process of creating the voter lists. With the final certification of the election results on November 1 (Oct 31?), and the short appeals window to close (today), this issue will certainly come up - especially because of the effect it had on turnout and electoral threshold results.

If the CEC is vindicated, having performed as admirably in voter registration as it has in conducting and tabulating the votes, then we can look at the 2010 Kyrgyz election results as the first "true" representation of free Kyrgyz political participation. In this event, we would rightly ascribe the discrepancies from the historic Kyrgyz trends - 70%+ participation, 2.6 Million voters - as manipulated aberrations.

However, if irregularities are discovered, or even if doubt remains in the absence of registration transparency, parties like Butun Kyrgyzstan will righteously maintain their grievances, and the legitimacy Kyrgyzstan is struggling to attain will remain just out of reach.

But What Does It Really Mean?

First, it must be admitted that, of all its elections, Parliamentary elections always have lower turnout than Presidential elections. Historically, we could ascribe this to the fact that the Jorgorku Kenesh, parliament, whether in its uni- or bi-cameral form, was always of secondary importance to a strong centralized President.

This would align with the earlier assertion - backed strongly by the 2010 ODHIR preliminary report - that the low turnout figures present a more accurate reflection, not a less engaged citizenry.

As for the increase in the voter lists, there are reasonable explanations that both support and deny paranoid accusations. For starters, even using the final 2010 Parliamentary voter list tally of 3,002,508 we must acknowledge that the Kyrgyz population is almost twice as large - 5.5 million - and that many of the 2.5 Million unregistered citizens would be eligible to register if they so chose. In light of this figure, the potential for dramatic increases in the total number of registered voters is easily explained - even expected - if the populace suddenly became more enthusiastic about national politics. Dramatic regime change and internal ethnic violence would both qualify as such motivators.

In this light, a 200,000 person increase (7% of registered voters, but only 0.5% of the population) doesn't seem extreme at all. That is - until you compare it to voter increases in the past.

Between 2000 and the July 2010 Constitutional Referendum, the total number of registered Kyrgyz voters increased by only 190,754 (actually, from 2000 to 2009, it increased by 344,787, but was then reduced following Bakiev's removal when 245,983 named were rejected as invalid/unverifiable).

In 10 years, the Kygyz voter lists grew by less than 200,000. In the last month of the election, it creased by more than 200,000. Understandable why Butun Kyrgyzstan refuses to accept this as a natural occurence of increased Kyrgyz voter enthusiasm.

But was it anyway?

Conclusion

What it comes down to is this - in the face of a logically possible increase in Kyrgyz citizens wanting to register, then declining to vote, and an undeniable track record of improper tampering of voter lists - the question is, in this 2010 election, can we trust the Central Election Committee or not?

The evidence of voter list tampering under the semi- and increasingly authoritarian regimes of Bakiev and Akayev were noted by international observers, but in the face of blatant voter intimidation, ballot stuffing, multi-voting, and outright fabrications in the tabulation phase, earlier ODHIR reports have always mentioned voter list irregularities, but rarely made them a major focus. Under the previous electoral system, the number of registered votes was only indirectly relevant, as elections required 50% voter turnout to be valid. This of course could be easily achieved by fraudulent registrations casting illegal ballots - often in bulk - but there was no incentive to inflate registration numbers without also contributing to the active vote count.

In the post-Bakiev era, when international election observers credit the CEC with an overall very positive rating for their conduct, administration, and transparency of the vote itself, serious questions are being addressed for the first time to the process of creating the voter lists. With the final certification of the election results on November 1 (Oct 31?), and the short appeals window to close (today), this issue will certainly come up - especially because of the effect it had on turnout and electoral threshold results.

If the CEC is vindicated, having performed as admirably in voter registration as it has in conducting and tabulating the votes, then we can look at the 2010 Kyrgyz election results as the first "true" representation of free Kyrgyz political participation. In this event, we would rightly ascribe the discrepancies from the historic Kyrgyz trends - 70%+ participation, 2.6 Million voters - as manipulated aberrations.

However, if irregularities are discovered, or even if doubt remains in the absence of registration transparency, parties like Butun Kyrgyzstan will righteously maintain their grievances, and the legitimacy Kyrgyzstan is struggling to attain will remain just out of reach.

No comments:

Post a Comment